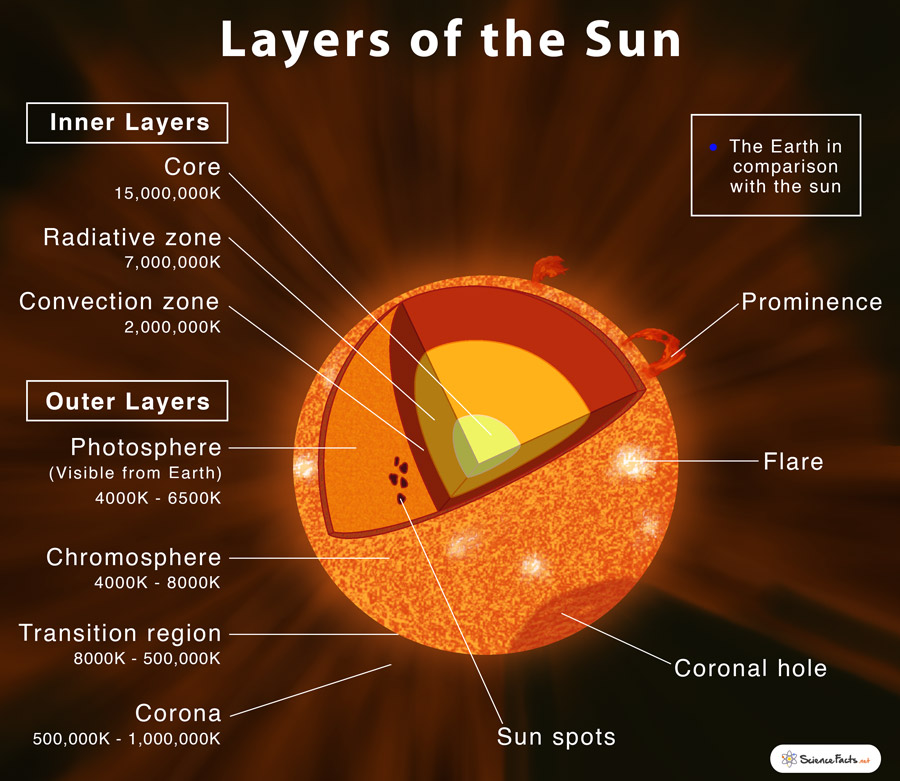

The Sun has 2 main sections that consist of a total of 6 main layers (3 layers per section). The first section of the Sun is it's atmosphere, which contains the Photosphere, the Chromosphere, and the Corona. The other section of the Sun is it's interior, which contains the Convective Zone, Radiative Zone, and the Core.

The Sun's Atmosphere:

Photosphere

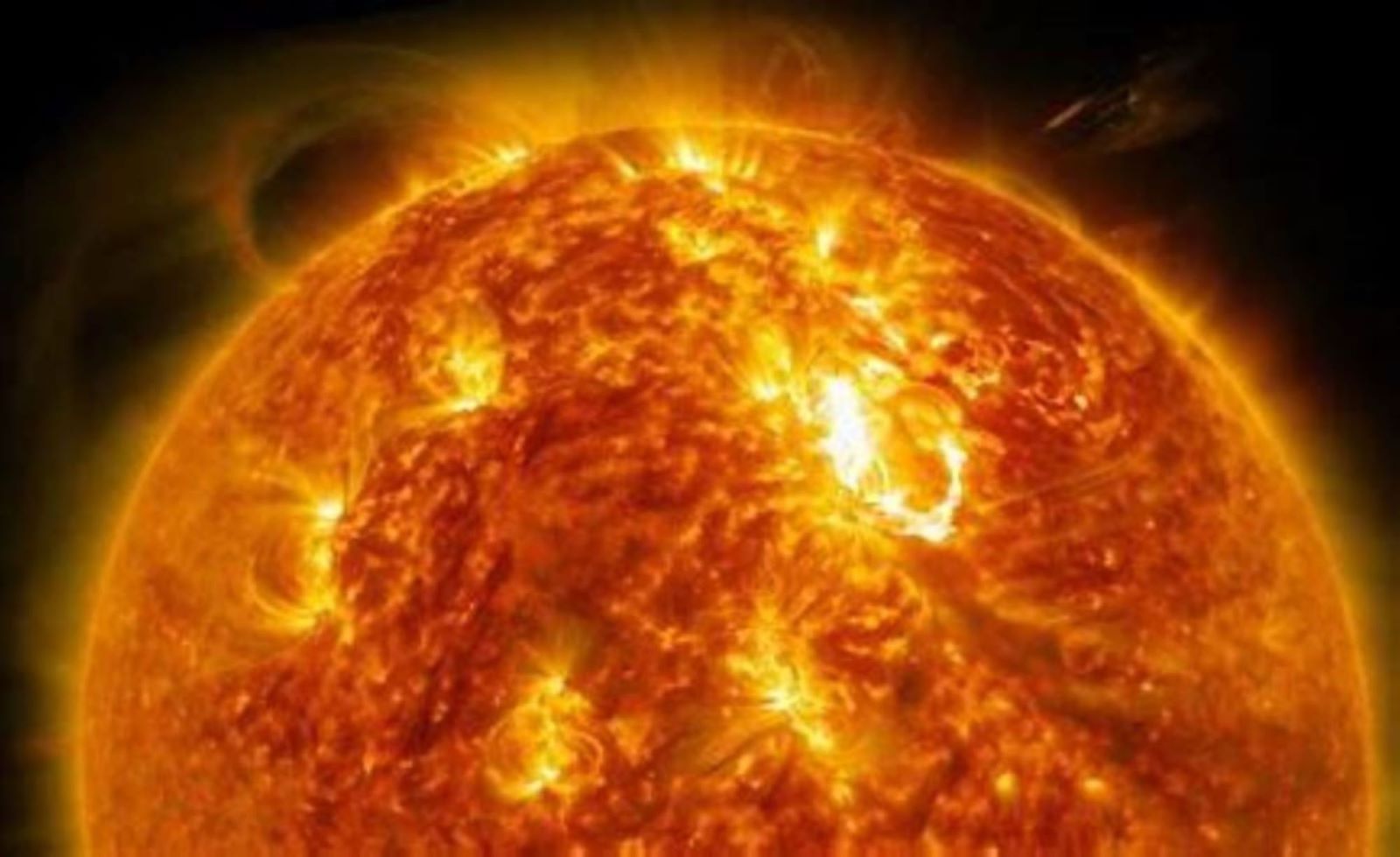

The photosphere is the Sun’s outermost visible layer, where most of its light and heat are emitted into space. It is approximately 500 kilometers thick and has an average temperature of 5,500°C (9,932°F). This layer is characterized by granules, small convection cells that transport heat from the Sun’s interior to its surface, creating a constantly shifting pattern. The photosphere is also home to sunspots, which appear as darker, cooler areas caused by intense magnetic activity that inhibits heat flow. Beyond the photosphere, the Sun’s atmosphere becomes more diffuse, while below it, the Sun is completely opaque to visible light, making this layer the boundary between the Sun’s interior and its surrounding atmosphere.

Chromosphere

The chromosphere is a thin layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, extending roughly 2,000 kilometers above the photosphere. Its temperature starts at around 4,000°C near its base but rises with altitude, reaching up to 20,000°C. This temperature increase is unusual compared to most layers, where heat typically decreases with distance from the core. The chromosphere is best observed during a solar eclipse, appearing as a reddish rim due to hydrogen emissions. It is a highly dynamic region, home to spicules, which are thin jets of plasma shooting upwards, and solar prominences, large, looping structures of solar material shaped by magnetic fields. These features highlight the chromosphere’s role in solar activity and its connection to the outer layers of the Sun.

Corona

The corona is the Sun’s outermost atmospheric layer, extending millions of kilometers into space. Despite being farther from the Sun’s core, it is unexpectedly hotter than the layers beneath it, with temperatures soaring above a million degrees Celsius. The corona is best observed during solar eclipses, appearing as a glowing white halo surrounding the Sun. This region is the birthplace of the solar wind, a continuous stream of charged particles that spreads throughout the solar system, influencing planetary atmospheres and magnetic fields. It is also the source of coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—massive eruptions of solar plasma and magnetic energy that can impact Earth’s space environment, sometimes disrupting satellites and power grids. Scientists are still investigating the mechanisms behind the corona’s extreme heat, making it one of the most intriguing regions of the Sun.

The Sun's Interior:

Convective Zone

The convective zone is the outermost layer of the Sun’s interior, stretching from about 70% of the Sun’s radius to the photosphere. In this region, temperatures gradually decrease from around 2 million°C near its base to 5,500°C at the surface. Unlike the radiative zone, where energy moves outward slowly as radiation, the convective zone transports heat through convection currents. Hot plasma rises toward the surface, cools as it loses energy, and then sinks back down, creating a continuous cycle of motion. This dynamic process is responsible for the granulation pattern observed on the photosphere, where bright and dark regions indicate the movement of hot and cooler plasma. The convective zone plays a crucial role in shaping surface features such as sunspots and solar flares, driven by the Sun’s complex magnetic activity.

Radiative Zone

The radiative zone is a vast region of the Sun’s interior, extending from 20% to 70% of the Sun’s radius. Temperatures here range from 2 million°C to 7 million°C, creating an environment where energy is transported primarily through radiation. Unlike the convective zone, where heat moves through fluid motion, energy in the radiative zone slowly migrates outward as photons (light particles). These photons undergo a process called radiative diffusion, repeatedly bouncing off particles in a zigzag pattern, which significantly slows their journey. In fact, it can take thousands to millions of years for a single photon to pass through this zone before reaching the convective layer. This slow energy transfer is crucial in regulating the Sun’s stability and ensuring a steady output of light and heat into space.

Core

The core is the Sun’s central and most crucial region, extending to about 20% of its radius. It is an extreme environment with temperatures reaching 15 million°C, where nuclear fusion takes place. In this process, hydrogen atoms fuse together to form helium, releasing an enormous amount of energy in the form of light and heat. This energy gradually moves outward through the radiative and convective zones before reaching the surface and radiating into space. The core’s fusion reactions are what power the Sun, providing the light and warmth necessary for life on Earth. Without this continuous energy production, the Sun would not be able to sustain itself or influence the solar system as it does.

*Did you want more detailed information about the Sun? If so, Visit Here.